A Topografia das Lágrimas

(original: The Topography of Tears).

O

projeto de Rose-Lynn passou a chamar-se A Topografia das Lágrimas,

através dele, ela estudou 100 lágrimas diferentes e descobriu que

existem muitas diferenças nas lágrimas de acordo com o nosso sentimento.

Cada gota de lágrima carrega um microcosmo de experiência humana. Com a

ajuda de Joseph Stromberg, da Faculdade de Artes e Ciência de

Smithsonian, Fisher tomou conhecimento de que existem três tipos

principais de lágrimas: basais (aquelas que o corpo produz para

lubrificar os olhos),

reflexivas e psíquicas (desencadeada por emoções).

“Emotions are not just the fuel that powers the psychological mechanism of a reasoning creature, they are parts, highly complex and messy parts, of this creature’s reasoning itself,” philosopher Martha Nussbaum wrote in her incisive treatise on the intelligence of emotions, titled after Proust’s powerful poetic image depicting the emotions as “geologic upheavals of thought.” But much of the messiness of our emotions comes from the inverse: Our thoughts, in a sense, are geologic upheavals of feeling — an immensity of our reasoning is devoted to making sense of, or rationalizing, the emotional patterns that underpin our intuitive responses to the world and therefore shape our very reality. Our interior lives unfold across landscapes that seem to belong to an alien world whose terrain is as difficult to map as it is to navigate — a world against which the young Dostoyevsky roiled in a frustrated letter on reason and emotion, and one which Antoine de Saint-Exupéry embraced so lyrically in one of the most memorable lines from The Little Prince: “It is such a secret place, the land of tears.”

“Emotions are not just the fuel that powers the psychological mechanism of a reasoning creature, they are parts, highly complex and messy parts, of this creature’s reasoning itself,” philosopher Martha Nussbaum wrote in her incisive treatise on the intelligence of emotions, titled after Proust’s powerful poetic image depicting the emotions as “geologic upheavals of thought.” But much of the messiness of our emotions comes from the inverse: Our thoughts, in a sense, are geologic upheavals of feeling — an immensity of our reasoning is devoted to making sense of, or rationalizing, the emotional patterns that underpin our intuitive responses to the world and therefore shape our very reality. Our interior lives unfold across landscapes that seem to belong to an alien world whose terrain is as difficult to map as it is to navigate — a world against which the young Dostoyevsky roiled in a frustrated letter on reason and emotion, and one which Antoine de Saint-Exupéry embraced so lyrically in one of the most memorable lines from The Little Prince: “It is such a secret place, the land of tears.”

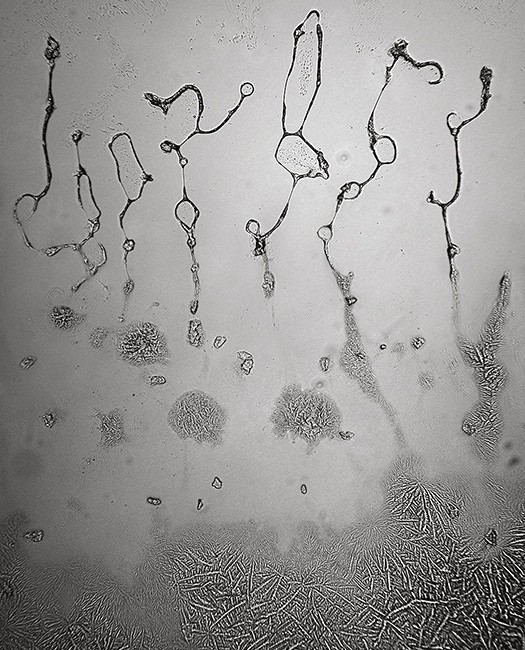

The geologic complexity of that secret place is what photographer Rose-Lynn Fisher explores in The Topography of Tears (public library) — a striking series of duotone photographs of tears shed for a kaleidoscope of reasons, dried on glass slides and captured in a hundredfold magnification through a high-resolution optical microscope. What emerges is an enthralling aerial tour of the landscape of human emotion and its the most stirring eruptions — joy, grief, gladness, remorse, hope — reminding us that the terra incognita of our interiority is better trekked with an explorer’s benevolent curiosity about the varied beauty of the landscape than with a conquistador’s forceful intent to control and sublimate. (Artist Maira Kalman affirmed this notion with great simplicity and poignancy in a page from her marvelous philosophical children’s book: “If you need to cry you should cry.”)

Building on her previous mesmerizing photomicrographs of bees, Fisher uses the technological tools of science to probe the poetic, immaterial dimensions of a universal human behavior radiating infinite emotional hues. Most of the tears she photographed are her own, but she also looked at those of men, women, and children from different backgrounds, crying for a variety of reasons. Accompanying each photograph is a caption ranging from the descriptive to the lyrically abstract — tears of compassion, tears of grief, tears of remorse, “tears for those who yearn for liberation,” “tears of elation at a liminal moment.”

In the introduction, Fisher reflects on the symbolic undertones of this inquiry into “the intangible poetry of life,” a project nearly a decade in the making:

Though the empirical nature of tears is a composition of water, proteins, minerals, hormones, and enzymes, the topography of tears is a momentary landscape, transient as the fingerprint of someone in a dream. The accumulation of these images is like an ephemeral atlas.[…]Tears are the medium of our most primal language in moments as unrelenting as death, as basic as hunger, and as complex as rites of passage. They are the evidence of our inner life overflowing its boundaries, spilling over into consciousness. Tears spontaneously release us to the possibility of realignment, reunion, catharsis, intractable resistance short-circuited… It’s as though each one of our tears carries a microcosm of the collective human experience, like one drop of an ocean.

Fittingly, the book features a short essay on tears by the poet Ann Lauterbach, who observed in another beautiful meditation on why we make art that “the crucial job of artists is to find a way to release materials into the animated middle ground between subjects, and so to initiate the difficult but joyful process of human connection” — a perfect articulation of the heart of Fisher’s project. In her essay for the book, Lauterbach writes:

“For a tear is an intellectual thing,” the great subversive 19th-century poet William Blake wrote, railing against the Deists, classical and contemporary; he believed they had stripped religion of its signal call for forgiveness, assigning too much authority to a single God and making human life untenable in its guilty abrasions. Tears are intellectual because they come from thoughts that spill over the body’s containing well; they are the secretion of excess we assign to emotion; perhaps emotion itself is simply caused by a surfeit of thought. One tries to unbind these durable dualities, to allow for the morphological shift that might allow the human creature to be complex but integrated, not divided into anatomical parts, all nouns and no transitive verb. We are not yet mechanical, technological things, we are intellectual — thinking — beings, and we cry when stirred beyond the capture of signifying Logos, which relents into flows of passionate silence. Perhaps this flow is the very proof that we cannot put our feelings in one place and our thoughts in another, the bleak result of a certain rationalism that threatens to overtake our civility — our capacity to forgive — and wants to make all ideas into abstractions, rigid and blunt, free of secretions.